Because we offer a transition to school program through our kindy and pre-kindy studios, from time to time, our educators and early childhood teachers are asked, ‘when are you going to teach my child to read?’ to which our answer is, we already are! But perhaps, not in the way parents expect.

The expectation from parents sometimes seems to be that your child will finish their time with Little Scholars and walk into prep knowing how to read, but that’s not exactly our aim.

Learning to read really starts from infanthood, and is a big process. In fact, research has found newborns’ brains are prewired to be receptive to seeing words and letters. This means babies are already getting ready to read at birth. The relevant part of the brain, known as the “visual word form area” (VWFA), is connected to the language network of the brain, and was discovered by researchers at Ohio State University, who analysed the brain scans of 40 one-week-old babies, as part of the Developing Human Connectome Project.

Researchers compared these to similar scans from 40 adults who participated in a separate Human Connectome Project. The VWFA is next to another part of visual cortex that processes faces, and it was reasonable to believe that there wasn’t any difference in these parts of the brain in newborns. Because as visual objects, faces have some of the same properties as words do, such as needing high spatial resolution for humans to see them correctly.

But the researchers found that even in newborns, the VWFA was different from the part of the visual cortex that recognises faces, primarily because of that connection to the language processing part of the brain.

Lead researcher Zeynep M. Saygin’s team is now scanning the brains of three and four-year-old children to learn more about what the VWFA does before children learn to read.

Research has also showed babies can differentiate their native language from another language when they’re only hours old, which means they begin processing language in the womb. And, amazingly, studies have also found that at birth, the infant brain can perceive the full set of 800 or so sounds, called phonemes. Phonemes form every word in every language.

People can’t learn to read without understanding language, so your child has been working on learning to read since birth!

How Little Scholars helps your child with language development

We encourage language development in many ways understanding that oral language is a significant aspect of early literacy, educators engage in song, rhyming and make use of picture books, to tell a story. Through our discussions and interactions with the children, and observations watching children play and what they’re interested in, we extend on their interests as part of our educational and intentional approach. So, for example, if educators see two children playing with toy dinosaurs, they may chat with them about why they’re interested. Then, they may have a conversation with the class about who else might be interested in dinosaurs. Based on the conversation, if many of the children are, they may set up sensory experiences, art opportunities and get relevant books on the topic of dinosaurs and read them together.

We also use words visually for many of our activities, even if they aren’t book-related, so that children begin to recognise words and associate them. Our environments place great emphasis to embed literacy print across all play spaces, this supports rich language experiences. Educators model words through children’s play, for example, when a child is engaged in block play, the educator will discuss the activity with them, exposing children to words, such as ‘you are putting a block on the top,’ (or underneath, or on the side.) These elements of language are also known as ‘positional language’ and introduce children to literacy and elements of numeracy at the same time.

From language development to learning to read

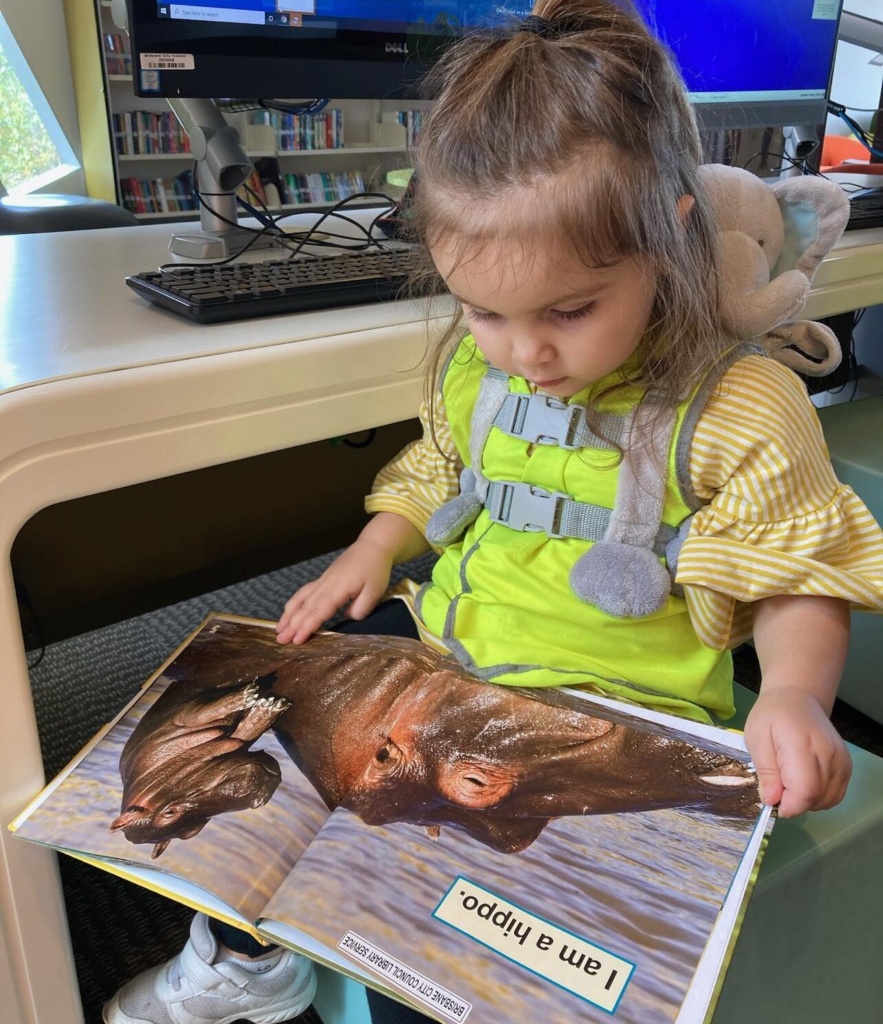

At Little Scholars, we have a specific approach to learning to read. It’s called the 3a Abecedarian Approach Australia to reading. This is where children are active in conversational reading.

A long 1970s study in the US was the basis for the now well-adapted approach. The Abecedarian Project was a controlled scientific study of the potential benefits of early childhood education for disadvantaged children. Children born between 1972 and 1977 were randomly assigned as babies to either the early educational intervention group or the control group.

Children in the experimental group received full-time, high-quality educational intervention in an early learning setting from infancy through age

- Educational activities consisted of “games” incorporated into the child’s day

- Activities focused on social, emotional, and cognitive areas of development but gave particular emphasis to language

- Children’s progress was monitored over time with follow-up studies conducted at ages 12, 15, 21, and 30

- The young adult findings demonstrate that important, long-lasting benefits were associated with the early childhood program

At the age 30 follow-up study, the treated group was more likely to hold a bachelor degree, hold a job, and delay parenthood, among other positive differences from their peers.

How our reading approach works

The 3a Approach encourages the adult and child to go ‘back and forth’ in conversation. There are three main levels to try – the first level is seeing, then showing, then saying.

Make it a conversation by asking your child to do something and not always following the words in a book.

“Can you see an owl? “Can you say owl?” “Can you show me an owl?”

At Little Scholars, we start with comprehension when looking at books – the thinking and talking about and enjoying the books we read together either in a group or one-on-one. Once children have a connection to books and reading, that’s when we can start teaching the ‘word parts’ of being a reader.

This is also something parents can and should do at home. Working with families is a core part of the Abecedarian approach! Parents are their children’s first educators, so we believe it’s to support families to grow in confidence as their children’s first educator, and reading together daily supports successful young readers. If you’d like to learn more, talk to your children’s educators or your campus manager for more information.

Read more: