For anyone who’s ever tried to learn a new language, you can probably attest to the fact it’s challenging. You think in one language and translate into another. There are new tenses, jargon, sentence structures, plurals versus singular words, never mind having the muscular movement necessary to form words with your mouth, the confidence to speak – we could go on and on. Now imagine what it could be like for a baby or small toddler?

There are benefits of course for children learning their mother tongue, or even a second language compared to adults learning language. According to German researchers, the melody of newborn babies’ cries is shaped by the sounds of their native language, which they hear in utero. Babies even babble in their first language. Wait, what? Meaning, from a very young age, they start copying the sounds and rhythms of the language they hear around them. This means they begin to use the same ups and downs in their voice (intonation) and the same timing as the language spoken at home. Plus, when babies babble, they often use the most common sounds (like consonants and vowels) from their family’s language. As babies continue to develop, their babbling starts to sound more like conversation, referred to as jargon, with a rhythm and tone resembling adult speech.

Fascinating, isn’t it?

So, how can you help your baby learn to speak? First, remember babies all develop at different ages and stages, so while some of their peers may be speaking, others may be more focused on movement, fine motor skills or something completely different.

Babies learn to communicate by listening to the people around them, especially their parents. They will:

Chatting with your baby is important, and it’s even better when it’s just the two of you. When it’s just parent and baby, without other adults or children around, baby talk can really work its magic. And when your little one tries to chat back, give them your full attention – it shows them you’re interested in what they have to say, and they’ll be encouraged to keep going.

It’s important to note that too much screen time isn’t great for babies’ language development. Australian and international guidelines suggest that children under two should ideally have no screen time, except maybe for a bit of video chatting. After all, your baby will find you way more interesting than any screen!

It’s great to use that sing-song baby talk voice, as babies love it. But don’t forget to mix in some regular, adult conversation too. Hearing how words are used in everyday talk is a big part of how your baby learns language.

You might know by now that it’s Little Scholars philosophy that children learn best through play. So with that in mind, we had some ideas about how you can play with your baby and help him or her learn to speak at the same time.

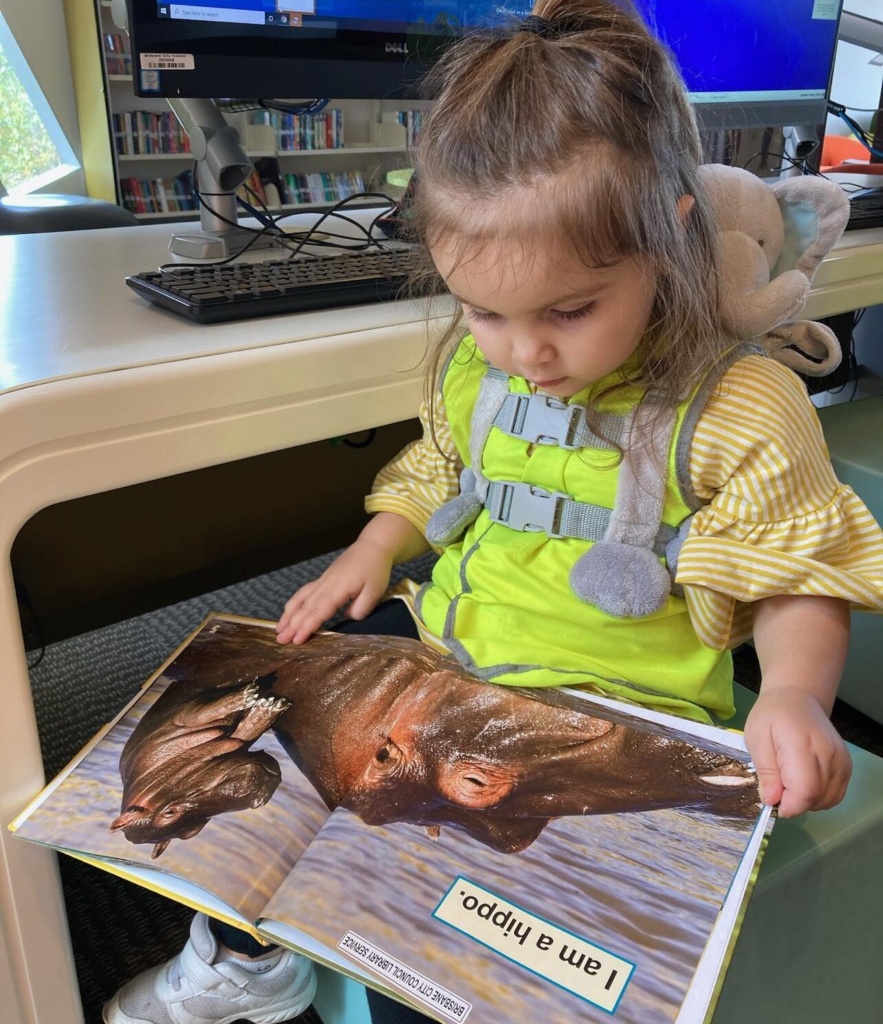

Sasha is a lead educator in one of the toddler studios at Little Scholars Burleigh. She says the Abecedarian Approach is one of her favourite tactics for supporting language development, especially when she’s reading with just one or two children.

“It’s a great way to have back and fourth conversation, for example ‘I can see a horse, can you show me where the horse is?’ or ‘I can see you’re pointing to a monkey, can you find anymore monkeys?’ another one could be ‘I can see you’re point to a dog, what noise does a dog make?’

“It’s not only conversational reading,” Sasha continues. “But also just communicating throughout experiences, if a child is stacking a block on top of another block communicating that action that the child is doing.”

Nikki, the lead educator in the nursery also at our Burleigh campus, says utilising one-on-one periods during routines and rituals, such as nappy changes, washing hands and faces, sunscreen times, are a great time to be talking to the children about what they have been and are doing, ‘we are putting our sunscreen and hats on so we are sun-safe to go outside,’ for example. They also name body parts during the process.

“We always warn the children if we are about to touch their bodies in order to help them, like for nappy changes or sunscreen application, and dictate what is happening to them, so we are verbalising every step,” Nikki says.

“We also talk through the steps at rest times as we place the children in their cots or walk into the cot room, saying ‘we are going to rest our bodies and have some sleep now, I will see you when we wake up and we will do ___’. Basically, we are constantly narrating to the children their every move,” Nikki says.

At our Deception campus, Hayley, lead educator of the toddler studio, does the same thing, but adds a little twist.

“I do a lot of singing, and turning things into songs!” says Hayley. We think that’s a great idea, research shows that singing can help with language development, memory, and even emotional regulation. Singing also has many physical benefits, like improving breathing and posture, and help with early literacy.

“I also think it’s important to be at the child’s level. Talking clearly, and using simple sentences, as well as showing interest when they are speaking to you,” Hayley adds.

Social media can be a great source for parents, so when it comes to baby speech, we’ve got a few we recommend.

Firstly, for all things child-development and early learning, @littlescholarsearlylearning

Then specific for children’s speech development tips, tricks and support, we like these Instagram accounts:

Remember, if you’re worried about your child’s speech development, talk to your GP who can advise or help you with next steps to support your child.

Speech development chart information from Speech Pathology Australia

Because we offer a transition to school program through our kindy and pre-kindy studios, from time to time, our educators and early childhood teachers are asked, ‘when are you going to teach my child to read?’ to which our answer is, we already are! But perhaps, not in the way parents expect.

The expectation from parents sometimes seems to be that your child will finish their time with Little Scholars and walk into prep knowing how to read, but that’s not exactly our aim.

Learning to read really starts from infanthood, and is a big process. In fact, research has found newborns’ brains are prewired to be receptive to seeing words and letters. This means babies are already getting ready to read at birth. The relevant part of the brain, known as the “visual word form area” (VWFA), is connected to the language network of the brain, and was discovered by researchers at Ohio State University, who analysed the brain scans of 40 one-week-old babies, as part of the Developing Human Connectome Project.

Researchers compared these to similar scans from 40 adults who participated in a separate Human Connectome Project. The VWFA is next to another part of visual cortex that processes faces, and it was reasonable to believe that there wasn’t any difference in these parts of the brain in newborns. Because as visual objects, faces have some of the same properties as words do, such as needing high spatial resolution for humans to see them correctly.

But the researchers found that even in newborns, the VWFA was different from the part of the visual cortex that recognises faces, primarily because of that connection to the language processing part of the brain.

Lead researcher Zeynep M. Saygin’s team is now scanning the brains of three and four-year-old children to learn more about what the VWFA does before children learn to read.

Research has also showed babies can differentiate their native language from another language when they’re only hours old, which means they begin processing language in the womb. And, amazingly, studies have also found that at birth, the infant brain can perceive the full set of 800 or so sounds, called phonemes. Phonemes form every word in every language.

People can’t learn to read without understanding language, so your child has been working on learning to read since birth!

We encourage language development in many ways understanding that oral language is a significant aspect of early literacy, educators engage in song, rhyming and make use of picture books, to tell a story. Through our discussions and interactions with the children, and observations watching children play and what they’re interested in, we extend on their interests as part of our educational and intentional approach. So, for example, if educators see two children playing with toy dinosaurs, they may chat with them about why they’re interested. Then, they may have a conversation with the class about who else might be interested in dinosaurs. Based on the conversation, if many of the children are, they may set up sensory experiences, art opportunities and get relevant books on the topic of dinosaurs and read them together.

We also use words visually for many of our activities, even if they aren’t book-related, so that children begin to recognise words and associate them. Our environments place great emphasis to embed literacy print across all play spaces, this supports rich language experiences. Educators model words through children’s play, for example, when a child is engaged in block play, the educator will discuss the activity with them, exposing children to words, such as ‘you are putting a block on the top,’ (or underneath, or on the side.) These elements of language are also known as ‘positional language’ and introduce children to literacy and elements of numeracy at the same time.

At Little Scholars, we have a specific approach to learning to read. It’s called the 3a Abecedarian Approach Australia to reading. This is where children are active in conversational reading.

A long 1970s study in the US was the basis for the now well-adapted approach. The Abecedarian Project was a controlled scientific study of the potential benefits of early childhood education for disadvantaged children. Children born between 1972 and 1977 were randomly assigned as babies to either the early educational intervention group or the control group.

Children in the experimental group received full-time, high-quality educational intervention in an early learning setting from infancy through age

At the age 30 follow-up study, the treated group was more likely to hold a bachelor degree, hold a job, and delay parenthood, among other positive differences from their peers.

The 3a Approach encourages the adult and child to go ‘back and forth’ in conversation. There are three main levels to try – the first level is seeing, then showing, then saying.

Make it a conversation by asking your child to do something and not always following the words in a book.

“Can you see an owl? “Can you say owl?” “Can you show me an owl?”

At Little Scholars, we start with comprehension when looking at books – the thinking and talking about and enjoying the books we read together either in a group or one-on-one. Once children have a connection to books and reading, that’s when we can start teaching the ‘word parts’ of being a reader.

This is also something parents can and should do at home. Working with families is a core part of the Abecedarian approach! Parents are their children’s first educators, so we believe it’s to support families to grow in confidence as their children’s first educator, and reading together daily supports successful young readers. If you’d like to learn more, talk to your children’s educators or your campus manager for more information.

Read more:

At Little Scholars School of Early Learning, we’re dedicated to shaping bright futures and instilling a lifelong passion for learning. With our strategically located childcare centres in Brisbane and the Gold Coast, we provide tailored educational experiences designed to foster your child’s holistic development.

Let us hold your hand and help looking for a child care centre. Leave your details with us and we’ll be in contact to arrange a time for a ‘Campus Tour’ and we will answer any questions you might have!

"*" indicates required fields